A History of the Delco Woods Park

By Doug Humes, January 2026

History of Delco Woods

HISTORY OF THE PROPERTY: THE 1600’s

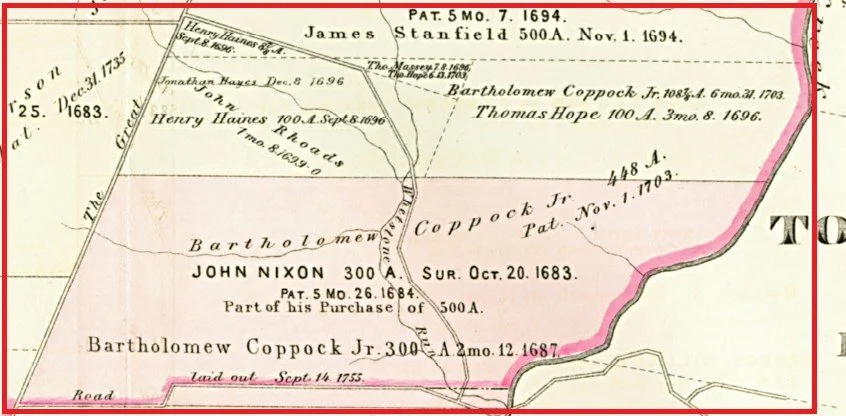

Marple Township was settled by English Quakers beginning in 1683. The Township was named after Marpool, England, where some of the early settlers were born and raised. This map shows the original grants related to the Delco Woods property. On the map, the “Great Road” at left is the current Sproul Road. The pink line at far right is Darby Creek, which serves as the border between Marple and Haverford townships. The road at top-left that angles through the middle of the property is the forerunner of Reed Road. William Penn sold parcels in England, but some were sold to real estate speculators who never took occupancy of the land, but would re-sell to others. In the grant map, the men who actually came to Marple and settled on these lands were John Rhoads and Bartholomew Coppock.

GEOGRAPHY OF PROPERTY

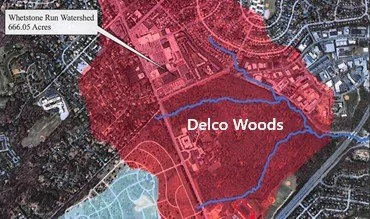

The Delco Woods property is an oblong property of 213 acres bounded by Reed Road, I-76 (the “Blue Route”) and Sproul Road in the southeast corner of Marple Township. Three streams run through the property, eventually joining and flowing into the Darby Creek near the border with Haverford Township. The primary stream on the property is the Whetstone Creek, one of the last remaining forested streams in the highly urbanized Darby Creek Watershed.

The property is largely wooded, with both relatively recent growth after the last farms were abandoned, and some old growth forest containing large majestic beech trees. The woods are home to deer, fox and a variety of other small mammals native to Pennsylvania.

The woods also contain traces of past agricultural and industrial use, including a tannery, whetstone quarries and factories, and demolished farm houses and out buildings.

HISTORY OF THE PROPERTY: THE 1700’s

Coppock Family: Bartholomew Coppock, Sr. (1638-1718) arrived from Cheshire, England in 1682 with wife Margaret Yarwood, and settled on the property around 1686. He built a home which was added to over the years. He and Margaret had four children, Jonathan, Bartholomew Jr., Hannah and Sarah. The house was used in 1686 for the Springfield Quaker Meeting, because the regular meeting place along Crum Creek was “back in ye woods too far.” Bartholomew Sr. was a farmer but also served as justice of the Court in Chester and a member of Penn’s Provincial Council. He gave nearby land across the township line in Springfield for the construction of a more convenient Springfield Friends Quaker Meeting House. The Coppock house was the home of generations of families for close to 300 years. After the Catholic Church bought the property, a series of tenants continued to live in the home and farm the property, but in 1965 the Church determined that the stone farmhouse they owned for close to 50 years was in “poor condition” and was demolished.

Rhoads Family:

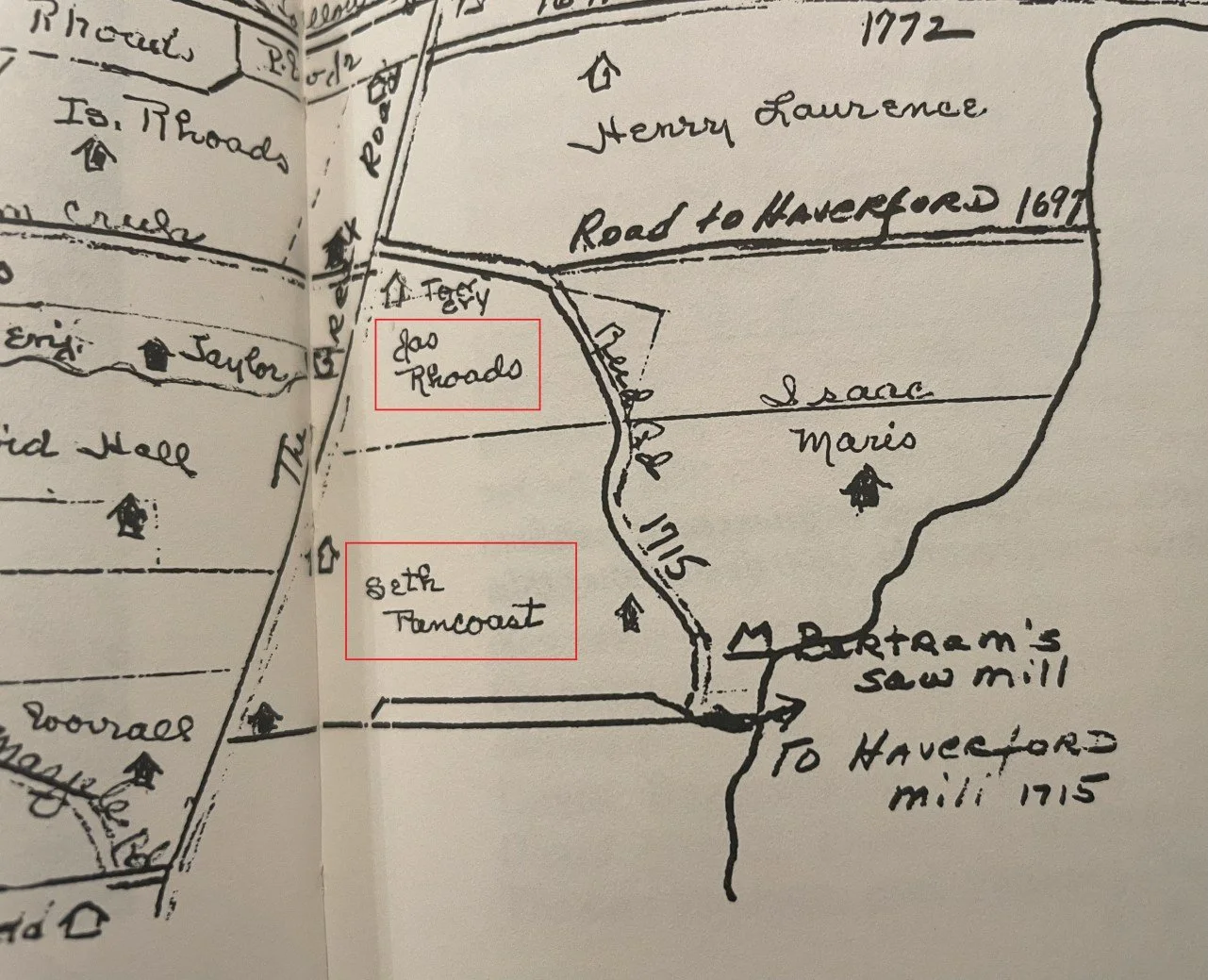

John Rhoads (1624-1701) was the original immigrant and landowner. He came from England around 1684 with son Joseph (1680-1732) among others, and built a home near the southeast intersection of Sproul and Reed roads. Son Joseph began a tannery operation at that location by around 1702.

In 1732, Joseph died. His wife, Abigail Bonsall, operated both the farm and tanyard until 1743 when their youngest son, James, came of age and received:

a grant of land containing 65 acres, 52 perches (rods) with the buildings, including the tannery, improvements and all rights, privileges and appurtenances involved

James (1722-1778) was married to Elizabeth Owen, and raised 10 children at their farmhouse. He continued the tannery business as well as farming. By 1774, Rhoads, the only tanner in Marple, had accumulated 192 acres of land, 6 horses, 9 cattle, and 1 servant—a rather prosperous homestead. Their son James Rhoads II (1748-1809) inherited the property and continued the farm and tannery business, but also discovered a source of whetstone rock on the property. During his ownership, James Rhoads added close to 400 acres and a scythe-stone quarry to his holdings.

Joseph Rhoads II died in 1809 and left the farm, tanyard and quarry to two of his sons, George (1780-1859) and Joseph III (1787-1851), who continued the business until the Civil War. The brothers farmed corn, pota-toes, oats, wheat and hay in the summer, and tanned in the winter. Quarrying operations continued year-round as weather permitted.

The tannery then consisted of 16 handlers, 5 leaches and over 40 vats, most of which were underlaid by wooden pipes or "trunks." A horse-powered pump facilitated the flow of liquids between vats through these pipes. In 1830 an early, stone edge-runner bark mill was replaced by one "constructed of iron," quite possibly of the coffee-grinder type. Again, horse power was utilized. A brook running through the property was diverted into a ditch to furnish, the tanyard with water.

The Rhoads employed a steady work force of 6 men, in addition to George and Joseph, at a time when the average tannery employed less than four workers. Referring to the tannery work force Jonathan E. Rhoads (1830-1914), Joseph's son, wrote in 1913:

In my earliest recollection previous to 1840 I can recall Richard Jacobs, George McLelven, Robert Wetherwill an apprentice as regularly employed in the tanyard and two colored men in the beam house. Also one currier, an expert hand.

Additional help could be drawn from the farm and quarry as needed. The tannery was, by 1840, a money-making enterprise; with an output of about 25 hides per week.

In 1851 Jonathan E. Rhoads entered the business with his father and uncle; by 1858, he was a full partner.

George died in 1859, and the firm was subsequently listed in Boyd's Business Directory as Joseph Rhoads and Son. Jonathan assumed full control upon his father's death in 1861. The outbreak of war in that year brought with it excellent business even though Rhoads, a Quaker, spurned the military market. Leather "sold as fast as it could be turned out at high prices."

Output had increased to over 100 calfskins and about 25 heavy hides tanned weekly. The lighter skins were purchased from a "salter" in Wilmington, who bought skins from a butcher, preserved them with salt, and in turn, sold the preserved skins to tanners. Beginning in 1863, the tanned leather was sold through John S. Wood, a leather merchant in Philadelphia. This arrangement continued as long as Jonathan controlled the business.

In 1867, Jonathan decided to move the tannery, by now the family's principal business (the scythe-stone quarry was depleted) to a new location. In August of that year, Phillip Garret, Rhoad's brother-in-law, wrote concerning a possible site:

I write to inform thee that the tanyard and business of Downing and Price at Wilmington are for sale and I thought thee might want to look into their availability for thy purposes, capacity of yard about 3,000 hides per year. My informant thought it a good business and that the firm had made a large amount of money at it.

Rhoads had dealt with Downing and Price for a number of years and apparently thought the venture worth-while. He purchased the tannery and moved his entire operation out of Marple and to Wilmington in 1868.

In 1887, Rhoads accepted his son, John, as partner. Eventually Rhoads’ other sons, Joseph, George and Wil-liam, entered the partnership, known as J. E. Rhoads and Sons. Through several more generations, the firm prospered. They opened a Philadelphia store in 1897 and branched to New York (1906), Atlanta (1923), and Cleveland (1927).

The Company continued in business through the 20th century. In 1983 John McGough joined J.E. Rhoads & Sons as chief executive officer, becoming the first person outside the Rhoads family to head the company since its founding. In 1993, a majority of the company's shares were sold out of the Rhoads family to an anonymous buyer, who moved its operations to an industrial park in Branchburg, New Jersey. The company went out of business in 2009. Up until that time, it has been considered the oldest continuously operated business in the United States.

In 1914, the Archdioceses of Philadelphia bought the old Rhoads tract and a variety of other properties to use as a cemetery. The Rhoads houses on the property were leased to tenant farmers who continued to oc-cupy the beautiful old stone homes. A long time local resident recalls in the early 1960’s that the tannery home tenant, “Farmer John”, would sell fresh vegetables from a roadside stand along Sproul Road.

In 1965, newspaper accounts say that despite a gentlemen’s agreement to preserve the Rhoads farmhouse as part of the approval of a sewer line for the new Cardinal O’Hara High School, the Archdiocese denied any agreement and demolished the farmhouse and all outbuildings.

In the woods today, not 50 steps from the entrance to Home Depot, the remnants of the Rhoads home and Tannery remain. Demolition reduced most of the home, barn and tan-nery buildings to piles of rocks, but left in place a large retain-ing wall with huge stone buttresses that continue to hold up the stone foundation walls as they have done for several hundred years. Perhaps hidden in those piles is the original datestone for the house.

Pancoast Family: The Seth Pancoast family came into possession of the Coppock farm by 1776, with some sources saying there was a marriage that tied the two families together. Generations of Pancoasts and Rhoads lived in the adjoining farms on the Delco Woods property until about 1909, when the Rhoads sold the old tannery property to the State Livestock Sanitary Board. In 1914 both the Rhoads and the Pancoast properties were purchased to be included as part of the Sts. Peter & Paul Cemetery.

As anyone who has lived in Marple Township knows, the Pancoast family has continued to live and work in the Township, including gen-erations who have carried the name Seth Pancoast.

In the 1940’s Samuel Pancoast operated a riding school in Marple, in addition to serving as superintendent of grounds at the Me-dia Court House and as Delaware County Sealer of Weights and Measures. Seth Pan-coast Sr. and Jr. operated Pancoast Gardens on West Chester Pike from 1959. Seth Pancoast III continues to operate the topsoil and mulch business on the same property that his grandfather, the blacksmith, housed his horse stables.

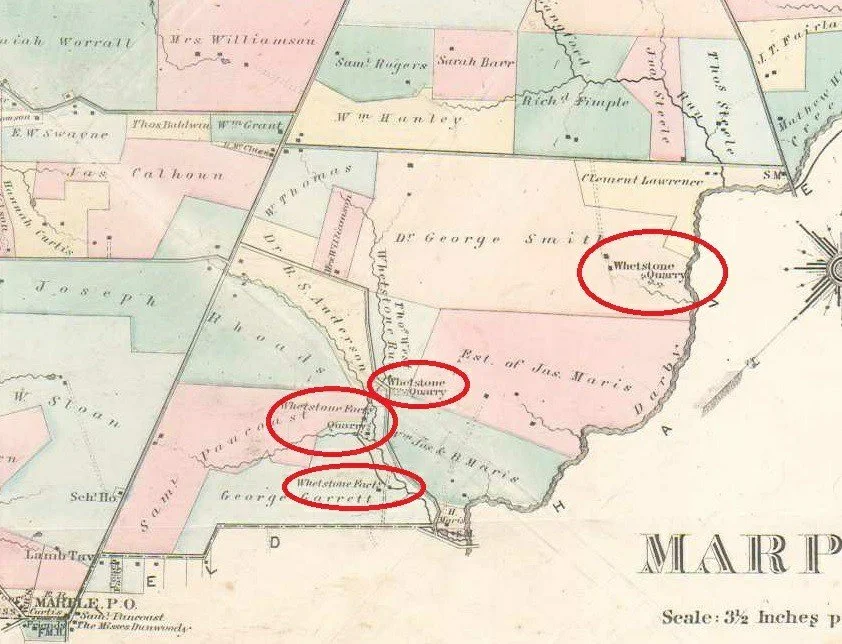

WHETSTONE QUARRIES AND FACTORIES

Sharpening stones, or whetstones, are used to sharpen the edges of metal tools and implements, such as knives, scissors, scythes, razors, chisels, hand scrapers, and plane blades, through grinding and honing. These stones come in a wide range of shapes, sizes, and material compositions.

Marple Township has seen several whetstone factories during its history. Remnants of some of those operations exist in the woods behind the former Don Guanella school.

An 1808 ad for the sale of the Estate of Seth Pancoast mentioned that an excellent whetstone quarry existed on the property. The Rhoads property also contained a whetstone quarry, and eventually the Rhoads Whetstone Factory, which operated from circa 1842 to circa 1874. The 1870 Marple census listed Norris Worrall as a “whetstone maker”. A 1905 newspaper article notes that Rose Tree Hunt had “the finest chase of the sea-son”, and noting that “the pack was coaxed across [the creek] into the Whetstone Quarry woods.” A 1990 article on what archeologists found beneath the Blue Route noted “A 19th century whetstone factory in Marple complete with piles of unused whetstones that had been discarded because they were slightly defective.”

HISTORY OF THE PROPERTY: 20TH CENTURY

St. Peter & Paul Cemetery (1914-current): The 1909 Marple map shows the various owners of the Delco Woods property as the State Livestock Sanitary Board (owning the former Rhoads home and tannery); a 121 acre parcel with house and farm buildings owned by the Estate of Samuel Pancoast; a 10 acre parcel owned by Patrick McPhillips; and an 81 acre parcel with home and outbuildings owned by William Algeo. All of these properties, as well as the 186 acre James Mullen farm across Sproul Road were purchased by the Arch-diocese in 1914 in what was reported as “one of the largest sales of ground ever made in Delaware County”. George J. Johnson was appointed cemetery superintendent. By 1926, there had been no burials as the property was being used as a farm to raise food to feed residents of Catholic Home for Girls on the property. The property on the west side of Sproul Road was chosen for the initial burials, and that property is today the active cemetery. The Delco Woods parcel was being held in reserve. However, there is a story told that the Delco Woods property had to in some way be consecrated or used as a cemetery—perhaps to preserve their tax exemption, and so at least one burial was made on the property. A long time resident recalls that there was a gravestone for that burial visible in the 1960’s, but with the abandonment of the old farms to woods, that stone has been lost from view.

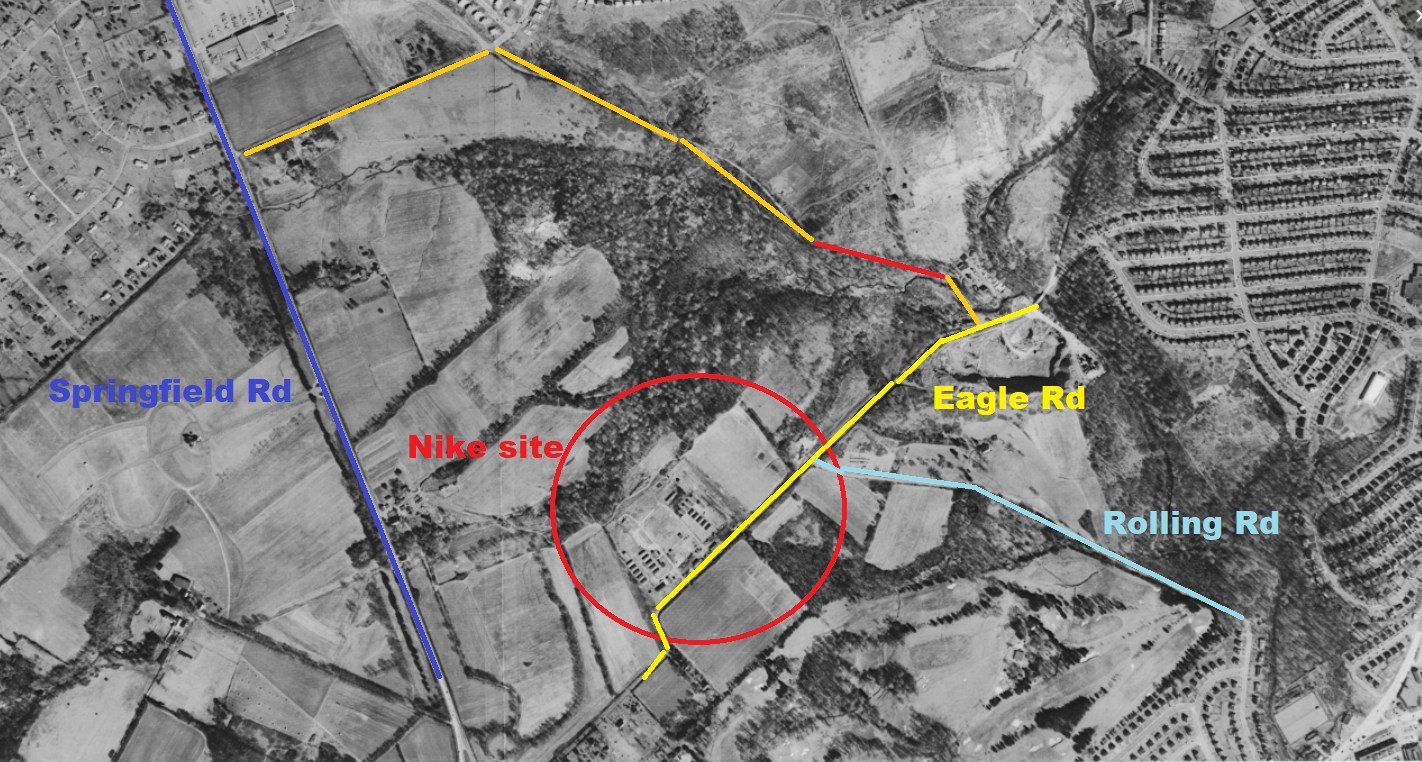

AAA Missile Defense Base (1951-1959): During the Cold War a ring of anti-aircraft bases were developed to protect Philadelphia. In the early 1950’s those bases were Anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA) gun batteries — typically radar-directed 90mm guns. One of those bases was created along Eagle Road on the southern boundary of the Archdiocese property. From about 1952-1959, men of the 51st AAA Battalion lived and worked in 14 buildings on the 15 acre base. The site consisted of multiple 90mm guns per site (often described as four guns per site), a radar/director setup to aim and time fire, and troop support facilities (barracks, mess, maintenance, etc.). Be-ginning in 1955, additional Nike missile ba-ses were built to protect the city, and the regular gun sites like Marple were closed. In the early 1960’s, Marple then leased the land from the Archdio-cese for recreational use. Part of the property was being used as baseball fields and for a midget care race-track. Later the Broomall Fire Department used the site for practice and the abandoned buildings were burned as part of the fire training. The site was then turned into sports fields for Carinal O’Hara High School.

HISTORY OF THE PROPERTY: 21st CENTURY

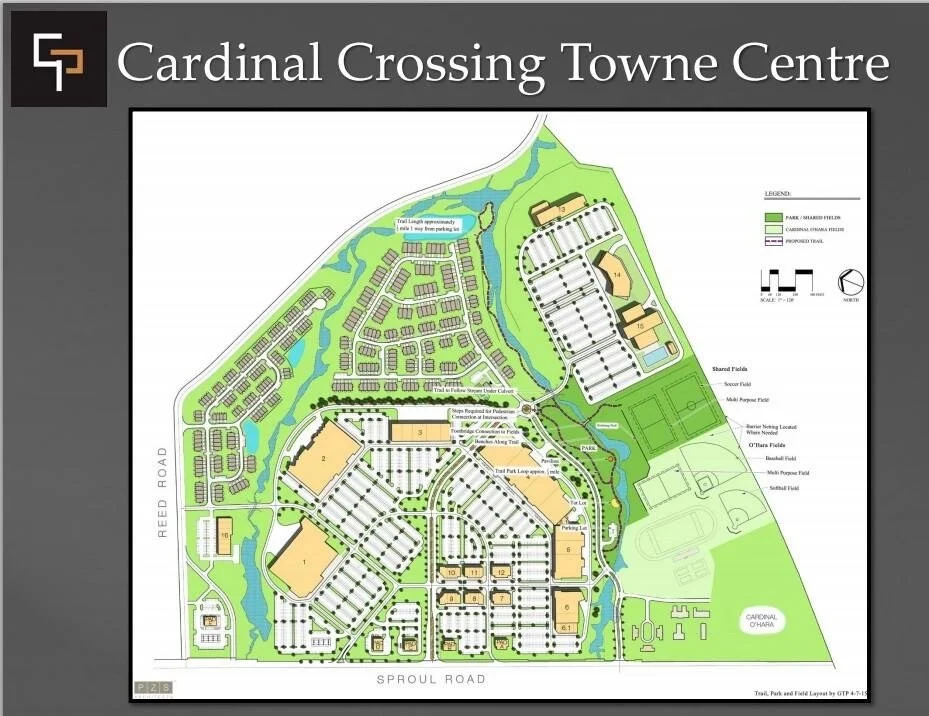

The Battle of Delco Woods (2014-2021): In the early 2000’s, with the exposure of the pedophile scandals in the Catholic Church, and resulting lawsuits and judgments, the Archdiocese stated selling off assets to raise money and conserve expenses. They offered the Don Guanella property for sale, and developers lined up to purchase it. When the first sale was announced in 2014, the project that was proposed would have used the 213 acres to build the largest shopping center in Delaware County, including 120 single family homes, 230 townhouses, a 150-room hotel, 55,000-square foot multiplex movie theater, 80,000-square foot recreational community center, Wawa convenience store with a 16-pump fueling station, 150,000 square feet of office space and 690,000 square feet of retail space.

HOW THE WOODS WERE SAVED

Property Conditions: The property has two streams, lots of interior steep slopes, and lots of trees. State and federal laws restrict what can be built in and around flood plains. The Township has a steep slopes ordinance which restricts what can be built in those designated steep slope areas. The township also has a tree ordinance which requires that a certain amount of trees have to be replanted when existing trees are removed from a property being developed. All of those factors made it more difficult and conceivably more expensive for a developer to use all 213 acres of the property for proposed uses. ware County’s largest park.

Cardinal O’Hara High School: In 1962, the Archdiocese announced plans to build a 4,000 pupil coeducational high school with 76 classrooms on a 35 acre site at Sproul & Eagles roads, to be named after John Cardinal O’Hara, the late Archbishop of Philadelphia who had died in 1960. The school opened for 1738 freshmen and sophomores in September of 1963, and when completed welcomed juniors and seniors as well.

Don Guanella School (1960-2015): In 1960, the Archdiocese announced that they would contract a school for in response to a growing recognition—still uncommon at the time—that children with significant cognitive disabilities deserved education, care, and dignity, not isolation. The school was named after Saint Luigi Guanella, an Italian priest known for his lifelong work serving people with disabilities and the poor. Don Guanella served boys and young men with significant intellectual and developmental disabilities, many of whom required full-time residential care. For decades, it functioned as both a school and long-term care facility, at a time when public special-education services were limited or nonexistent. With changes in how people with intellectual disabilities should be treated, the Don Guanella Village was largely phased out by 2014, with most residents moved to smaller homes and facilities in the community, but the archdiocese constructed additional residential buildings on the property near the high school for 27 medically fragile men.

BMX Bike Course (ca. 1980-current): Cardinal O’Hara High School at the southern end of the Delco Woods property has easy access to a trailhead into the woods from the athletic fields. Generations of those students have used the woods for teenaged activities: smoking, beer parties, dirt bike trails, and simply hanging out without any prying adult eyes. Beginning in the early 1980’s, with the rise of BMX bikes—small bikes capable of flying off ramps and doing acrobatics in mid-air—the students and other area teenagers began constructing a whole system of trails with dirt ramps to be used for BMX activities. Those trails still exist and are still in use at the south end of the woods.

Concerned citizens in Marple Township and surrounding communities began to question whether the proposed use was a good reason to destroy the woods. A grassroots organization, Save Marple Greenspace, was formed to better inform the township residents of what was proposed. People started showing up at public meetings to voice their concerns. Soon, the meetings could not be held in the township meeting room, and so they were moved to the high school auditorium. The Township officials took notice. The first development application was denied. A second developer stepped forward with a less aggressive proposed use of the space. Other developers waited in the wings. From 2014 until 2021, a variety of development proposals were made, and were ultimately rejected by Marple Township.

During that time period, Save Marple Greenspace explored whether a coalition of conservation groups and Delaware County could be successful in raising enough money to make an offer to the Archdiocese to purchase the property and conserve it. However, the initial development bid, reported at a price of $47 million, set unreasonably high expectations with the Archdiocese and an improbable price to be raised by a grass-roots organization.

In summer of 2021, in the midst of the Covid epidemic, Delaware County initiated eminent domain proceedings to acquire the land for public use, eventually purchasing it for $22 million. The County had received over $110 million in federal American Rescue Plan Act funds during the Covid epidemic to be used for County purposes. That gave them more options on how to pay for the land they had condemned. The County has committed to keep the land largely in its natural condition to be used as a county park. A parking lot was constructed on Reed Road to begin to accommodate park visitors. For the hikers, bikers, dog walkers and nature enthusiasts who have been visiting the woods for generations, as well as the local wildlife in the woods, the Park is just fine in its current state.

Zoning: Zoning laws limit what uses can be made of any particular property. The flattest and most valuable piece of the Delco Woods property is the road-front property along Sproul Road, as it avoids the step slope and water issues and is more accessible for public traffic. The existing zoning for frontage on Sproul Road was institutional—for Don Guanella and the High School. An institutional use does not permit shopping centers, and residential and commercial developments. So a developer could not use the property as a matter of legal right for its desired commercial use without asking the Township to change the zoning. The Township does not have to even consider that type of change. So a developer had no absolute right to make commercial use of the property without convincing the Township and the community to agree to that change.

Grassroots opposition: In 2014, green and white bumper stickers and yard signs started appearing on cars and lawns in the community. A group of concerned citizens had formed Save Marple Greenspace to educate and mobilize the community join the public discussion on whether they wanted to trade the woods and open space for a gigantic mixed use development. Hundreds of people began showing up at township meetings to voice their opposition. The Township Commissioners, under the scrutiny of jam-packed meetings, listened to concerns about traffic, air quality, water quality and downstream consequences, and held the developers to a rigorous adherence to the existing laws. The process took time, and in that time other solutions were found.

Politics: In the 2019 general election, three Democratic candidates won County Council seats, giving the Democrats a majority (and full control) of the five-member Delaware County Council for the first time since the Civil War. In 2021 that majority voted to acquire the property to make it Delaware County’s largest park.

Covid: Strange as it may seem, one of the most important reasons why the woods were saved was due to Covid and the federal governments decision to make funds available to state and local governments to ad-dress the economic effects of the shutdown. The funds given to Delaware County made the decision to ac-quire the property possible. For Delaware County residents, it is the amazing silver lining to the awful tragedy of the Covid epidemic.